|

| A zine page from Tales of the Elvis Clones. Warts and all. |

When I got started, computers were a thing, but not ubiquitous. For me and my friends, making comics in central Texas, everything was still done with Bristol board, pencil, and India ink. We did paste-up with Xeroxes and glue sticks. I learned to letter comics with an Ames lettering guide. We used proportion wheels to calculate how much to reduce artwork for printing. All things that take microseconds to do in Adobe Illustrator and Photoshop and InDesign. It was a different world.

But only in terms of production. Today’s all-digital marketplace means that there are no limits to how a project can look; indeed, there are ‘zines being produced now that have production values equal to or greater than a number of game publishers and small press outfits.

Ah…but what if you can’t pull that off? What if you have zero design sense? What if you have little (or no) budget for stuff like art? Buck up, little camper. That shit didn’t stop me (or anyone else) from making cool stuff back in the day, and it shouldn’t stop you, either. I can’t solve every problem, but I do have some general advice that you may be useful to you.

And just for grins I'm including several pages from my early zining days, to better illustrate that anyone can do this.

1. Embrace the Aesthetic

|

| Page 2 of Elvis Clones. Note the "ghosting" from the glue stick paste up. |

The fact that you’re making a ‘zine and not a glossy, printed-in-china hardcover book is to your advantage. Zines are supposed to be small. They’re supposed to be a little rough around the edges. Digitally produced ‘zines can still be rough, too, so don’t worry that your initial effort doesn’t look like something from Games Workshop. No one is expecting it to, especially if you lead with the format, i.e. this is a DIY medium. Zines are small, simple, and (relatively) cheap. It’s okay to be rough. It’s okay to be unpolished. Hell, as long as you are able to easily communicate your ideas, it’s okay to be handwritten!

Look at my sample pages on the right. Granted, that's the master and not the copy, so you can see all of the blue lines and so forth, but that's the point, right there. I'm NO kind of artist, and this effort really shows it. But it tells the story, and sets the tone for the rest of the issue. If I can do it, I guarantee you can do it.

There are a ton of resources out there for you to make use of. Copyright free public domain art (just be sure!) and inexpensive RPG game art are readily available to you.

|

| Xeroxes, acetate overlays...I used whatever worked. |

A great example of this can be found here: A Brief Study of TSR Book Design by Kevin Crawford. I wanted my zine, Monty Haul, to have a 1st edition D&D feel to it, and Kevin spent an obsessive amount of time backwards engineering the various fonts and layout styles that TSR used from the very beginning to 4th edition.

This lengthy and interesting (if you like fonts and graphic design) treatise is free on DTRPG. Free. Check it out; you’ll see he put in a lot of work, and he’s just giving it away. But that’s Kevin Crawford in a nutshell.

That one document really helped me make a lot of creative decisions that were otherwise holding me up. Now, Monty Haul bears little resemblance to the first edition Monster Manual, but there is something kinda charmingly clunky about it, mostly because of the inexpert ways I laid my zine out and the fonts I chose. I wouldn’t have been able to do that otherwise, and here’s the bonus: now that I am comfortable with those fonts and layouts, I am playing around with them in later zines.

2. Let Your Freak Flag Fly

|

| A spread from a quarter sized zine I created in the 90s. |

I mean, who even does that? How creative and cool! There were a lot of interesting zines that played with mechanics, with format, with subject matter, and there were also a shit-ton of OSR game content as well as system neutral stuff. One of the people doing incredible work in this regard right now is Philip Reed, a veteran of the rpg business. His zine, DelayedBlast Game Master, is chock-full of crazed nuttiness that you can roll up and stat on the fly, or plan things out with a little forethought. But his ideas are really different and interesting and have a great old-school feel to them.

Don’t be afraid to experiment. The more out there you go, the better. Push yourself. Don’t save your good ideas; put them in your zine. And this leads me to the next piece of advice:

|

| The cover, again, unaltered to show all of the paste up that went into something so disposable. |

I think this may well be the most important thing I have to offer. Zines, both then and now, are always best when they are little cults of personality. The best zines have a voice, and it should be yours. Your point of view is what makes the zine unique and readable. And frequently, it’s your voice and your tone that people will respond to the most.

Look, writing for game manuals is essentially technical writing, in that you’re trying to communicate concepts as simply and efficiently as possible. But the extra challenge for RPG game books is that you have to include flaming swords and wizards and shit. It’s a balancing act that a good percentage of people within the industry fail at doing.

So don’t try. Old school ‘zines like CometBus and Murder Can Be Fun were all about the tone. Gaming zines can (and should) also be a window into your personality; I mean, otherwise, why write anything? Present your ideas in your own way. It’s more honest, and it’s easier on you because you don’t have to pretend. Be yourself.

4. Stay Under Budget

|

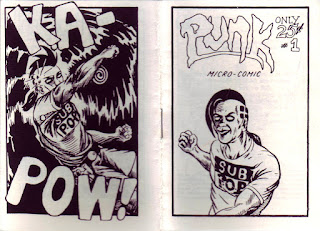

| These micro-comics were folded into halves, then quarters, then eighths. Double sided. |

This hobby, this cottage industry, this DIY activity? It’s a zero sum game, at best. There are folks out there that have parlayed their zines into books, and their books into fiefdoms unto themselves, which is fantastic and uniformly well deserved. That ain’t you. Not yet, anyway. You probably have little (or no) money to spare. Even though this isn’t a traditional publishing venture, it DOES tick all of the same boxes.

The goal here is to not lose any money. Breaking even is awesome. Making a little scratch? That’s heavenly. And the best way to make a little money is to not spend a lot of money. That might mean you have to use free public domain artwork instead of hiring your favorite Magic: the Gathering card artist.

|

| One of the micro-comics, unfolded and untrimmed. We were insane. But the cost was only 10 cents. |

You also might be worried that you don’t have enough content for a zine. Partner up! Find someone else who wants to put a zine out and see if they want to contribute. There are even artists who will work with zine creators and take large cuts in their usual rates to provide artwork because they love the hobby and want to give back.

The caveat to this is not to promise something you can’t deliver (like fat stacks of cash) and be honest and up front about what the work entails and how you can compensate others for it. Note: comp copies of your zine are akin to coin of the realm, here. Everyone likes to see their name in print. Sending a few copies to your contributors spreads the love around.

The other reason to keep costs down is so you don’t have to charge $37.83 per copy. A low buy-in will ensure that more people have a reason to pick it up. These days, it’s not uncommon for zines to price out at $10 or so. Digital editions should be much less, at least half your print zine price. And you absolutely should offer both. Digital editions almost always have a larger profit margin built in because there’s nothing to print or ship.

5. Join the Community

|

| The other side of Klops! #1. Once folded, the top edge was carefully trimmed and viola! A 16-page comic the size of a business card. |

This last piece of advice is also self-evident, and also increasingly essential in the 21st century. Using whatever platform you are least opposed to, make your presence known and seek out other zinesters. Hashtags are your friends, as are Facebook groups (there’s a great group on FB called RPG Zines). Network with your peers. Make friends. Do stuff together. This is really important because the DIY community and the zine community are very supportive of one another. They will help you, and you ostensibly should help them, like any thriving community.

It sucks to have to market yourself; most people are bad at it. The skill sets for marketing and game design are located in opposite hemispheres in your brain. So, if you can’t be Stan Lee and flog your own creations actively, do it passively. Hashtag your tweets. Add links to your signatures on message boards (do they still have message boards? I may be dating myself.) Change your profile pic to the cover of your zine. There’s a lot of little things you can do to keep your project close to your digital self.

Of course, if you can build a website, do that! Shopping cart software is baked into a lot of DIY websites right now. Use the site to build a list of emails you can blast when you do a new project (don’t spam!) and let folks know where it can be found. The downside is that these types of things do cost some money to set up and maintain. It’s the cost of doing business these days.

I hope this has been somewhat useful. There’s never been a better time to start creating RPG zines. Take a deep breath and cannonball into the pool; the water is fine.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.