I love talking about movies, both what they mean on the surface and what they are not saying deep beneath the crust. Talking about film is one of my favorite things to do. I also read a lot of film history books and try to keep up with the popular scholarship surrounding film studies. I’m not as deep in that as I would like—these past few years have made it difficult—but I consider it more than a hobby for me, and slightly less than an avocation. When I do write about movies (and other popular culture), I have three different approaches that I use:

Fannish

This is

usually an unapologetic gush, or a rush of “How cool was this?” moments. I

don’t use it too often, but it does come up from time to time, especially when

we’re talking about films that I love despite having a pretty nuanced

yardstick. Dinosaur movies. Movies with gorillas in them. Any movie with

pirates. My biases and predilections are on the record so there’s no real need

to re-hash them here. That’s not to say

I can’t BE critical of these movies, but I usually don’t, because I like to

give my brain a rest with old friends.

Critical

There may

well be complimentary things in this tone of voice, because I often use a

Good/Bad/Ugly structure, but I actively seek to get underneath what’s onscreen

and talk about why a film works or doesn’t work, or sometimes, what is says, or

doesn’t say. This tone, or something

very like it, is what most professional reviewers use when they trash Venom and praise The English Patient. My essays about film are usually in this style

and tone, because I think this is the sweet spot between Fannish and Scholarly.

Also, it’s a lot less work in that sometimes they will write themselves.

Scholarly

This style is

what I use when I’ve got a thesis to present and I am making a case for it. If

you had to write a research paper in high school or college, you know what I

mean. Sometimes, my tone is casual, and sometimes, my presentation is haphazard

(because, having presented papers at academic conferences before, doing it in

MLA style is a pain the ass), but I have a point and I’m going to walk you

through it.

In the case

of the above series, Finn’s Top 5 strikes a chord somewhere between Fannish and

Critical, and The Movies of Dungeons and Dragons comes in somewhere between

Critical and Scholarly. The Top 5 lists are subjective, and even though I state

my criteria up front, the list is modified by other lists, and also how closely

the movie cleaves to the subject. That’s just how my brain works.

With The Movies of Dungeons and Dragons, I have a specific intention that filters my

commentary; how impactful were these movies on First Edition Dungeons and

Dragons players? Specifically, me and my extended groups of friends and fellow

gamers? That’s a terribly specific lens to focus in on, but that’s okay,

because in scholarship, it’s not uncommon to look at a creative work from only

one angle or to judge it by a narrow criterion.

These lists have

always generated lively discussion amongst me and my friends (and you can join

in here on Facefook if you like). But there’s always one or two people who

become indignant or offended or just incredulous that I didn’t like A, or loved

B, or didn’t mention C, or they think I’m just plain wrong about D. Granted,

this is all subjective, because my trash may be your treasure, and vice versa,

and I think that’s well established.

It’s

important to remember that even amidst all of the subjective opinions about

movies, there are some measurable data points. I’m talking about bad movies,

and more specifically, the ability to identify and acknowledge that a movie is

bad, and also having the wherewithal to like it anyway. I think it’s perfectly

okay to like bad movies; God knows, I like plenty of them—entire genres and

sub-genres of movies, in fact. But I know they are bad. I accept that they are

bad. You can love an ugly dog, too. In fact, sometimes, you can love an ugly

dog more than you love a Kennel Club champion.

I’ve gotten

tired of the hipsters and film school dropouts who litter the Internet like

spilled Legos in a daycare center that have weaponized sarcasm and irony so

that they can employ the “It’s so bad, it’s good” defense. This allows them to

chatter excitedly like squirrels about, just to pick a movie out of a hat, Flash Gordon (1980), and still maintain

their “street cred,” whatever the fuck that is.

If you’ve

done your job correctly, a reader should be able to tell within three or four

paragraphs of your writing, approximately 250 – 300 words, if you’re

knowledgeable about your subject. And if you’re writing a 1,000 word piece on

the merits of Flash Gordon as the

alpha and the omega of bad science fiction, then your readers should not get to

the end of the article and think, “What is this asshole talking about?” or

worse, “That son-of-a-bitch, he just threw Flash

Gordon under the bus, man!” I’m not

saying that every online critic is bad at their job, but…well…okay…I guess what

I’m saying is that the vast majority of the self-styled “online critics” are

exactly that. And while we’re at it, probably 65% of all the print media film

critics are not that great, either.

There’s

something about being made the sole film critic for the East Haverbrook Picayne-Journal that turns some people into

blithering imbeciles. Something about taking that job makes them think they are

tastemakers for the whole of East Haverbrook (and the new West Haverbrook

development, where all the real landed gentry have flocked to) and start

championing Sony Picture Classics films and pooh-poohing genre movies, when the

biggest box office success story last year at the East Haverbrook Cineplex was the

remake of Stephen King’s IT. I agree,

that sentence sounds bizarre in the modern world, but you know what? That’s all

the more reason to discuss it. Why did something that had three strikes against

it—a remake, a Stephen King property, and a horror movie released in

September—suddenly become one of the biggest hits of the year? That’s worth

exploring, regardless of genre.

But film

critics tend to downplay anything that elicits a visceral response other than

all-consuming sadness or crushing ennui. Don’t believe me? Go look up the reviews

for Stephen King’s IT (2017) and

watch how every second paragraph begins with some version of, “But even with

all that going for it, the film is still…” and then there’s criticism about the

pacing, or the sameness of the scenes, or that Pennywise becomes a cartoon

after a while, or this, or that, or insert some film terminology here and there

to signal to your readers, “See? I wasn’t really scared, you guys.” I’ll bet

every single one of you a million dollars that there will be at least one major

news outlet that runs a story in 2019, after IT: Chapter 2 premieres in September, with the headline, “Does IT: Chapter 2 Forecast the Beginning of

Horror Movie Fatigue?”

Simply put,

these people have forgotten who they are writing for. A good reviewer can explain

a movie to an audience and communicate what’s good about it, what’s bad about

it, and whether or not that audience should spend their dough on it, and they

can do it while (a) not giving the plot away, (b) letting the audience know if

the movie is objectively good or bad, and (c) let the audience know if the

reviewer liked it despite (or because of) its flaws. That seems like a tall

order, but it’s really not.

A good film

critic is someone you can read and readily ascertain what they value in a film.

If they are consistent, you can even read a review about a movie they don’t

like and from their writing, decide if you will like it and make an informed

decision. That’s the job of a good reviewer; not to condescend or to impress

the reader with how much they know, but to use that knowledge to inform the

reader about what they have seen. There are many print journalists who are good

at this. There are not a lot of Digi-Critics who are. But when you go onto

sites like Rotten Tomatoes, you don’t get to pick which critics you want to

hear from. They lump everyone in together in an aggregate, and so that’s why

there’s almost always a disparity between what critics think about movies, and

especially genre films, and what fans think about movies.

However,

having said all of this, let it be known that genre movies can be, and

frequently are, bad. Badly conceived, badly written, badly acted, badly

directed, badly produced, you name it. This is a lesser concern in 2018, but

throughout the rich history of the cinema, i.e. most of the twentieth century,

bad movies are legion. And that’s okay. Not everything can be Citizen Kane. Or Gone With the Wind. Or Casablanca.

It’s why those films are considered classics; the cream rises to the top. Great

movies withstand the test of time, whilst bad movies simply go away…unless

rescued by a group of passionate fans who see something more in a movie, or

maybe it speaks directly to this sub-group, or it becomes greater than the sum

of its parts. You know what I’m talking about: the “cult classic.”

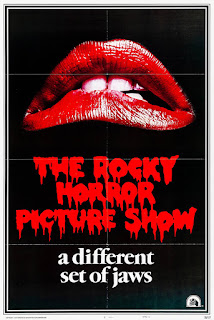

The best

example of this is The Rocky Horror

Picture Show (1975). Without the yelling and the audience participation,

the movie is pretty awful—but it’s nearly impossible for people to look at that

movie now in any kind of critical vacuum. It has completely transcended its

original intent: that of a film adaptation of a stage play that champions as

well as subverts B-movies, in particular science fiction B-movies of the 1950s and 1960s. No one

watches The Rocky Horror Picture Show to examine Richard O’Brien’s commentary

on the movies of his youth. Cult classic.

In Part 2 of this essay, I'm going to take apart a beloved cult classic to show that a bad movie can still be a good thing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.